This past week, after reading about it for several years, mostly in glowing terms, I had the chance to see Pedro Costa’s most recent film, Vitalina Verela (2019). It had screened at that year’s Locarno Festival, winning Best Film, and its lead character, of the same name as the film, won Best Actress. It subsequently became a hot item on the festival circuit. I haven’t been to festivals for some time, so I missed it. But, as things “opened up” here in Boston I was informed it would be screening at Cambridge’s famed art house, the Brattle, and I grabbed the brass ring and booked tickets.

I know Pedro a modest bit, meeting him a few times, chatting a bit. Not enough time to say “a friend” – more an acquaintance. He says he likes (some of) my films, and I have liked his and seen I think most of them. Haven’t seen the one about editing with Straub-Huillet. We shared together a quick recognition of what digital video offered, and both jumped on it early. Myself in 97, Pedro in 99.

So after the lavish critical praise, and the prelude of having much appreciated his past films, I went in anticipation of a cinematic treat.

Opening with a long Lav Diaz type shot, looking down a narrow alleyway, distant figures slowly approach the camera and pass. Not clear at first, it is later understood this was a funeral cortege. In his opening gambit Costa sets the terms for this film: it will be slow and measured; very slow, very measured.

As usual in his more recent work, the film is far less about “a story” than about atmosphere and tone, and the poetic aura this generates (or doesn’t). In brief “the story” is that of an immigrant woman from the former Portuguese colony Cabo Verde, arriving 3 days late in Lisbon for her husband’s funeral, and from that unfolds in minimal form, a kind of backdrop, which we are told in voice over – her husband had left long ago, to make money; he was a scoundrel, and now Vitalina is stranded in Portugal where, as she is reminded, “there is nothing” for her.

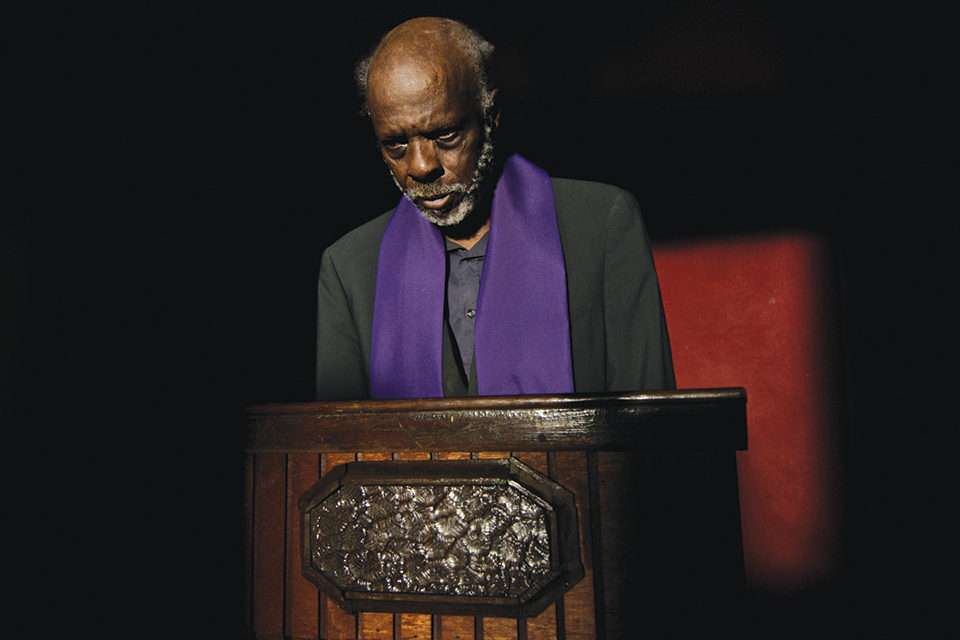

Around this thin thread Costa constructs his film in a sequence of usually long static takes, carefully considered and lit tableaux, echoing for the most part certain art of the 18th century, most closely the work of Iberian artist Francisco de Zurbarán, one of the many artists of the time deeply influenced by Caravaggio. Set in deep shadow, Costa orchestrates his images as if paintings – much remarked upon and noted by critics, with exclamations about its “jaw-dropping” beauty. Like Caravaggio, the realist who used peasants and showed the grime and grit of “real life” in his work, while draping it in extravagant if subtle and discreet lighting. Costa and his cinematographer Leonardo Simões aim for a realism using carefully controlled and false lighting, no less so than Hollywood. However in a sense they invert Spielbergian back-lighting, with, in effect, the light behind the spectator illuminating the scene. Shadows tend to (very slowly) precede the entrance of a character, signaling with a kind of ghostly ponderousness the next utterance or silence on offer.

Occasionally the static images are punctuated with a slow tilt or pan – but very seldom. Rather we are led through a sequence of very formal images, some of which recur as a motifs, with a religious solemnity given to the most elemental of things. Vitalina arrives off the airplane from Cabo Verde with bare feet. The preacher’s hand holds a pole, the frame of a door, passes by a wall. The frame of a crude confessional recurs a number of times. Doors creak open and closed, providing momentary slashes of light. Each image is given an iconic weight. Faces, hands, things, bodies – all heavy with gravity. With seriousness.

Step by step Costa builds his liturgy, establishing a slow and solemn cadence in which the film is transformed into a quasi-religious ritual, as if counting rosary beads. The rhythm is measured in repeated images. The characters are simultaneously monumentalized in long close-ups, their faces stoic and motionless, and rendered lifeless. The occasional voice-over is repeated in slow paced words, some incantatory; others filling us in on the background story of Vitalina and her errant husband Joaquin. Cumulatively these all combine to make for a vaguely hypnotic flow in which the characters float, devoid of control or decisiveness, hidden in Costa’s mostly oscura and very little chiaro. His seeming intention is to induce the spectator into a slo-mo trance, drawn along not by drama or “action” but by submission to the lethargic pacing, actors frozen in place in fixed tableaux, bodies standing in to represent or perhaps in Costa’s view, simply “being.” Following Bresson’s dictum, his actors are reduced to models, who shuffle listessly, casting diffuse shadows on the grim walls, muttering near indecipherable phrases (I sincerely doubt Portuguese speakers can understand half of what is said and subtitled), or standing immobile, staring out of the dim shadows to which they are condemned.

In this sombre shadow-play, sound is accentuated in a Bressonian sense: doors squeal shut and open; feet shuffle on rough floors, objects are set on a table; in the far distance from these distinct sounds the voices of the streets and alleyways float as if miles away. Costa’s figures are entombed in a claustrophobic world of shadows talking to themselves, most often in almost inaudible mumbles, such that the handful of times when a voice speaks out loud it comes as a shock.

In composing his film, Costa has, certainly intentionally, genuflected to the tropes of the religion of his world – Catholicism, particularly of the Iberian Peninsula. The film is a kind of Stations of the Cross, with Vitalina assigned the role of staring out mournfully from the screen, lamenting her fate, and the fate of her people, hidden in the shadows, hopeless. She kneels and sorrows at the foot of her own cross and crucifixion. In phrasing his film in these terms, Costa gives his work an built-in lever on the spectator, which is well-trained in how to behave in a cathedral, or a major art gallery: with hushed reverence. The hovering cloak of seriousness hangs overhead. We don’t buy popcorn when going to a Pedro Costa film. And we don’t make wise-cracks as a religious procession passes by, never mind the preposterous proposals that religion offers up: a virgin birth by a holy fuck (!) spawning a tri-part god who sent himself to save the world from itself and is crucified for his bother, and then ascends to the heavens there to dispense (depending on which sect of the subsequent established religion one chooses to believe) harsh punishments or “love” to those who embrace and follow him. Belief suffers no rational quibbles or examination – you do or you don’t believe.

In wrapping himself in the aura of religious severity, Costa has inoculated himself against criticism from his most ardent “fans” – Pedro can do no wrong. Hence one watches in sombre seriousness, as his procession passes by, and we watch as Vitalina watches her life go down the drain. The supplicants wash themselves in the sadness of her life, and her stoicism in the face of her fate; it is a form of absolution or flagellation: I watched, ergo I am good.

This is one of the tricks of the religious trade (and many others). If one does it – in this case watch a Costa film – it somehow makes one good for having watched the misery he is showing. Just like being of the slim minority of people who, say, watch a serious documentary about some serious subject, usually about something you already know about and already agree with its sociopolitical slant, and so you learn little or nothing, but you receive the benediction of a shared belief: it does nothing in the real world outside of Plato’s cinema, but it makes the celebrants feel good about themselves. In intimate relations this is called masturbation.

Unfortunately this all congeals, like the religious ceremonies it is aping, into an ossified ritual, emptied of the intended meaning. In religion this signifies the moral corruption of the institutions, reducing the original life-pulse which gave birth to the given religion into empty if solemn gestures. In art, including cinema, this often turns to an inward fold, in which the artist regurgitates their own tropes, and drives them toward an indigestible self-parody (Godard, Greenaway, Straub-Huillet and others), looping their particular look/shots/mode of presentation and purported principles, again and again – instantly recognizable as theirs, but increasingly less interesting except to disciples. In Costa’s case it has evolved into a form of very humorless self-parody, his apparent obsessions(s) having swamped the life out of his stoic subjects, now cast in tableaux in which they stand posing, or shuffle in the shadows, their faces often obscured, standing in for the weeping figures at the foot of the cross.

In attempting to illuminate the lives of his characters and their world, Costa’s severe aestheticism instead kills them. Where Costa says he makes these films to give voice to the lives of these immigrants, instead he confines them to a narrow aesthetic trap, his aesthetic trap, far more limited than the socio-political realm to which they are confined in reality. The truth is that precious few people will ever see this film, and of those who do most live in an esoteric realm in which cinema is a bizarre host, in which watching movies, it is believed, will give you insight into the truth of life, a delusion which they share with their fellow cineastes. Costa – by his own admission – grew up in a cathedral, the Cinemateca Portuguese, ingesting his communions there, where he learned the vast catechisms of the cinema and came away with a litany of things he’d learned. He puts these on display for those in the know, a nod to this great name and and that and then another, for the priests to decipher and nod approvingly. Like Biblical citations or the Torah.

As it happens, I have lived in Lisboa a bit, and in the late 90’s visited Fontainhas when it was alive, a favela of homemade houses, mostly of immigrants from Cabo Verde, but also others. It was indeed a place of drugs and booze (just like classier neighborhoods), and it was very poor. But as other similar places around the world, it was also lively, colorful, energetic. As it were, compared to the dour Portuguese surrounding it, it had “rhythm” which came with the African source of its residents.

In Costa’s portrayals, commencing with his early 35mm films, this liveliness is largely absent and in Vitalina Verela, it is utterly absent – perhaps the men playing cards in the suffocating shadows being the only exception. So while Costa claims to be giving these people a voice, showing them to the world from which they are hidden, he is not really doing so; rather he is imposing his grim dour view upon them and claiming it is their voice. Just like colonialists always assert they are doing good for those they have occupied, bringing them salvation through Christ or capitalism. Of course Pedro would counter that his entourage of regulars are full participants, voluntarily sharing this work, and hence it is an expression of themselves, and not just Pedro’s vision. And in the muffled confines of the inner sanctum of his church, this will likely beget assent. As colonizers invariably find reason to ethically and morally take the high ground in their own minds.

Vitalina Verela comes to its dour conclusion with a final entourage, heading to the cemetery, down the same alley which we saw in the first shot. We’ve come full circle, ashes to ashes. Only at the film’s conclusion do we find a glimpse of daylight, among the graves and mausoleums, where the immigrants’ burial places are marked with numbers, erased in life and in death. As if a flashback we are then afforded a glimpse of Vitalina’s home in Cabo Verde, a mountain top place of cinder-block and concrete, with vertiginous peaks behind it, the Valhalla she left behind to face her personal hell in Lisbon.

In Portugal there is a concept, which once you understand it, seems tangible in their society and culture – the concept of saudade. This is a feeling, a sensibility which draws from a nostalgia for something absent or lost, or even something which never was; it comes as a sadness to be heard in the music of fado (fate), and something which pervades Portugal’s culture. I was once told it derived from the disappearance of King Sebastiao in the Battle of Alcazar in 1578, and his failure to return, which, supposedly the Portuguese have waited for ever since. Or perhaps it is a reverie for the long collapsed empire. Whatever its sources, as one who lived there and felt it, it certainly pervades Portuguese culture, in its arts and in every day living.

Pedro Costa provides a perfect embodiment of this saudade quality in his films, most particularly in Vitalena Varela, where his solemnity pervades each frame. In turn we might say that he imposes his Portuguese colonial imperialism on his characters, dressing them in darkness, weighing them down with a somnolent pace in which they are suffocated and condemned to perdition, surrounded with a small chorus of extras who stand immobile as the glaze of sticky amber congeals about them.

In reducing Vitalina into a religious icon, the stoic body and face (which won “Best Actress” in Locarno) set in a looming darkness, Costa has sucked all her vita out and left an impressive shell. Some have suggested this film is a kind of horror film. Or perhaps vampire, the Portuguese empire still taking gold from its victims?

At the screening (late afternoon of two screening), with the beating heart of America’s training ground for the elite of its empire, Harvard University, a very short 3 minute walk away, the audience was composed of five people, including me and the two friends I invited to come see it. Neither of my friends liked it.

There is a cure for everything; it is called death.

Portuguese proverb

One thought on “Santo Pedro and Vitalina”